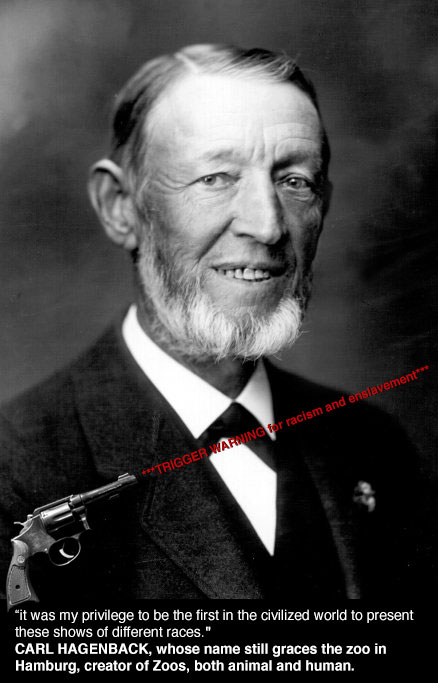

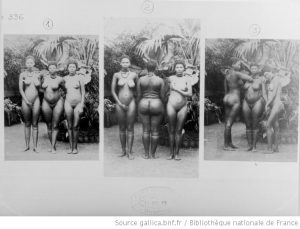

I saw something the other day. On the Hottentot Venus wikipedia page, there was a copy of an advertisement, not well sourced. I was looking into the often told story of fashion being influenced by the Khoikhoi body type. Namely the bustle, that thing that protrudes at the back of dresses from the 1800s, when it came into fashion. Are you lost yet? It gets worse. Apparently there was another famous “hottentot” who was around at the same time as Saartjie Baartman. But, her body wasn’t treated the same, or maybe she lived a long and happy life, or something… her name has disappeared, but I found a reference to her existence somewhere in the archives and went on a hunt for her name and lost the original reference in the process but learned a lot more on the other side. And, as an aside, “hottentots” were shown for a really long time. I have a hard time with all the ones we forget for how strong the memory of Saartjie Baartman is… but I understand. I really, truly, understand. It is why I can’t bring myself to post the very old pictures of the cast of her body that was in the Jardins, even though I know where that photo lives digitally. It hurts to see. But, there were more. And they displayed the men and children too. Here are some albums from the 1884 international exposition in Paris (I don’t remember there being images of the children here): http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b77023200.r=Hottentots%2C+album+de+31+phot.langEN http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7702319b.r=hottentot.langEN  My relationship with these images is complicated. I will be addressing it in my dissertation (and I addressed part of it in my article). I mean, that part is basically written… the nuts and bolts of it is this though is, often people chose to go to these expositions. We cannot know why. But, often times, these images that come from these awful practices are the only reflections we see of bodies that look like ours in the historical photographic archive. And if we can step out of the colonial framing for a moment, and look again, maybe we’ll see something else. Maybe we’ll even find a name. For instance, the woman on the right in this series of photos is named Bebye Rooi.The names of the other two have been lost to history. I know her name because of the amazing work of Deborah WIllis and Carla Williams, who use one of the photos from this series in their book “The Black Female Body: A Photographic History”.

My relationship with these images is complicated. I will be addressing it in my dissertation (and I addressed part of it in my article). I mean, that part is basically written… the nuts and bolts of it is this though is, often people chose to go to these expositions. We cannot know why. But, often times, these images that come from these awful practices are the only reflections we see of bodies that look like ours in the historical photographic archive. And if we can step out of the colonial framing for a moment, and look again, maybe we’ll see something else. Maybe we’ll even find a name. For instance, the woman on the right in this series of photos is named Bebye Rooi.The names of the other two have been lost to history. I know her name because of the amazing work of Deborah WIllis and Carla Williams, who use one of the photos from this series in their book “The Black Female Body: A Photographic History”.

Anyway, in the midst of my research I found plays that talk about the Hottentot Venus and how in love with her body people were from 1814. I read the play linked below about a man who is so enamored with the idea of Venus Hottentot that he refuses to marry his cousin. She meets a man who tells her how popular the body shape is in Paris. All the women are buying clothes and house coats that allow them to have a body in her shape. She buys one of these outfits. Her cousin immediately falls in love with her, and when the real Venus Hottentot arrives he accuses her of being an impostor.

Just found a play called “La Vénus hottentote, ou Haine aux françaises , vaudeville en un acte” http://t.co/YGNIcIXzJz

— Jade E. Davis (@jadedid) June 26, 2014

http://t.co/m3Yt4ooxgB here’s the entry for the street, and link again: http://t.co/ErD3AMB0Bf

— Jade E. Davis (@jadedid) June 27, 2014

I found a single reference to the “tournure hottentote” (hottentot bustle) in my initial French search. It was in a digest of court cases. The story is actually a little bit funny. A wife told her husband she was pregnant for the fourth time. He kicked her out of the house and sent her to the hospital and told her not to return home if she brought home another girl (they had three girls already). Well, luck would have it that she had a girl. And he didn’t let her come back. So with the help of a friend who had a key and had a neighbor who was on her side, when he was away she would have the neighbor go to the house and get her stuff, including a pot. The neighbor put the pot under her dress as he ran into her during one of these find and retrieve runs, in the back. He was very angry about the pot and said she looked ridiculous, with that pot giving her a “tournure hottentote” (you can read all about it here: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4514944.r=%22tournure+hottentote%22.langEN). Since my French search was turning up nothing, and I’d fallen down a black hole of research for the night on this weird historical representation

bizarre. Found a scifi-ish book from 1884, and the conversation changed completely. http://t.co/oEoormkEh4 will stop now — Jade E. Davis (@jadedid) June 26, 2014

This one was a bit painful because the idea of the body had gone from beautiful but grotesque (I think we understand grotesque but beautiful things) to monstrous… and it becomes monstrous at the time those three beautiful women above were in paris as well as the others in that album possibly. Anyway, after the French search I moved on to research in English. I found tons of photos American Bustles that mimic the shape, so I’m wondering if it was more an american fashion thing (will need to find a fashion scholar to ask). But something else happened… I looked up “hottentot bustle” and learned that it is medical short hand for Steatopygia, the medical term for having a completely natural body shape. The shape is described as having a backside that looks like it belongs to a wholey different body. But.. these women, men and children existed and exist. That’s why I think these photos are important.

Steatopygia (hottentot bustle)… http://t.co/YmrMnI8f8A I don’t know what to do now. I think I took in too much information. — Jade E. Davis (@jadedid) June 27, 2014

and it hurts that this is the medical terminology. That is from 1994, so 20 years ago. So I did another scholar search and found medical references as recently as 2011 that call it the hottentot bustle.. and I learned that hottentot apron is the shorthand for elongated labia, or Hypertrophy of the labia minora, because that is something that was also common amongst the tribe. Another “medical condition” to describe perfectly normal bodies. That term also has an article from the 2010s, but I didn’t bookmark it and don’t care to look for it right now. So… a search for a name and a fashion reference (which yes, i found some in Vaudeville, but have not yet found a hard link to it changing fashion), led to finding out a bunch of other disturbing stuff. But it’s the stuff that makes me think it’s important that we see the image above for what it is, and for what it could be. I write about image 3 in my dissertation (if you click through on the image you can see a bigger version). The women are linked, they are embodied, and they are there. For some they might be an oddity, but for someone like me, and many others, it is one of the few occasions I see my body reflected back historically. And, despite the circumstance, their heads are high. They aren’t some marvel of modern medicine. They are just there. And they are beautiful. And I am thankful that I know they existed, even though I will only ever know the name of one. I never did find the name of the other famous “hottentot” from the early 1800s… she’s lost to a few historical footnotes.