I was very excited to finally get my hands on the Decolonization: a very short introduction because I freaking love these short little books. Me being me I did the thing that I always do. I looked for Fanon on the index, and then read so I can figure out if the author and I align politically. On the one page that quotes Fanon it quickly became apparent that we do not. He states, and I quote, “Fanon was clearly wrong: some colonial regimes yielded to their subjects’ demands for independence without being coerced to do so by violence”. Hashtag sad face.

Holy bananas. So, yes, the first chapter of Wretched of the Earth is “On Violence”, but right from the get go Fanon places violence in things as banal as changing the name of a social locale or inviting certain people to events. The demand by colonial subjects for independence is an inherently violent act. Its a demand to break, destroy, and imagine something new. But we tend to not talk about the role of imagination in Wretched. If you look at the agenda on any conference engaging with Fanon, his call to violence is often called as a powerful prescription or a failed attempt to understand what it will take to decolonize. When I read Fanon though, I read him through his introductions, endings, and footnotes, the spaces where he often hid his utterances of hope. I cannot say this enough… to read Wretched of the Earth as a standalone book is weird. It is a follow up to Black Skin White Masks and you miss so much if you don’t read them together. Further, in the other books he wrote he comes down harder on what he really thinks fixes things: love and imagination.

The death of the author is a concept that looms over engagements with critical theory. This in an of itself is a colonial impulse. It is how theorists like Derrida, Althusser, and writers like Camus (all from families who had been in Algeria for centuries/generations), lost their Africaness and how Fanon, a Frenchman (who was stationed in Algeria but born in the old (a slave) colony of Martinique and educated in France) gained his. Fanon was French. The death of the author also allows us to erase the perspective and position that came with Fanon’s profession.

Fanon was a medical doctor, a psychiatrist, who wrote a thesis (required for his medical degree) working with neurologists and psychiatrist on how culture effects the manifestation of mental illnesses in Lyon. From there he went to a state run hospital in French Algeria (which was a part of France in the same way as Hawaii is to the US) at the end of their designation as département, as they were being decolonized. In this space he saw violence, the kind that is outlined in the BSWM and Wretched. He also knew that, like most psychiatric practices, to heal people would take even more (mental and sometimes self-inflicted/perceived physical) violence, and love, and imagination. To get people to love themselves and to transcend to a place that is not what colonization “says I am” which was the only message they receive is violent. To get the colonizer to acknowledge this? More (psychic) violence.

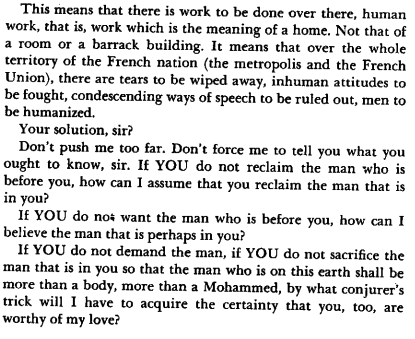

At times there will be physical violence, but more often than not, it is mental anguish. The impulse to latch on to violence reinforces existing stereotypes of the angry black man in Fanon… I think I think it is just a racist reading tbh because even though Fanon starts with “On Violence”, he ends with case notes “Colonial War and Mental Disorders”. Read that… and also read “The North African Syndrome“, a short essay that has an ending that is my reaction when people insist that Fanon was only about physical violence (without love or direction) shared below.

There is a violence in recognizing that there is a person that is oppressed, but they are not THE OPPRESSED. We are human. All of us. To acknowledge that when so much is wrapped up in that not being true, or people being less than, or, in this political moment in the country where I live, “animals”, is an act of violence toward the man who defines himself based on dehumanizing others. Fanon was not wrong. His reply to those who question if this is violence, who do not see that this requires a certain type of suffering and anguish, might be this beautiful ending.

Leave a Reply