The act of relegating something to History is a demand that it be both remembered and performed by society in order to ensure we exist within the same cultural context. That is to say, performance and memory were always already in History. History is sort of society’s “scriptive thing”, if you will. Working with Robin Bernstein’s “Dances with Things”, specifically the concept of the “scriptive thing”, I am playing with History. While I appreciate Bernstein’s article, and found the concept and place where she chose to engage with it amazingly helpful and necessary, I would like to move on to the next page. Rather than looking at the historical thing as re-enforcing the script, even as it troubles the script in asking us to dance, I would like to imagine a way to look at the historical thing as rescriptive. By rescriptive I mean seeing the historically scriptive thing as capable of taking the script of history and rewriting/reworking or even breaking it.

Taking History as a big scriptive thing that is being rescripted is daunting. However, it is something that needs to be done. Too often we are placed in affective positions towards history that take away our agency or ability to imagine things another way. Having a universal Historical script is proscriptive. The Historical script has to flatten the world, to ensure we all stay on script. This causes so many of us to get caught up in the what-have-beens by imagining a non-existent pre-time we nostalgically look back towards made up of what-could and what-should- have-beens. There is no time or place in history where things have been universally good or universally bad. While we can argue about better or worse, or go to that uncomfortable space of comparing wounds, I do not find that to be a generative space for rescripting. These conversations feel like “a photograph in which human and caricature appear equally flat and sharp” (88), because History is anything is caricature of societies.

History as a scriptive is more than just a script, it is a prescription, letting us know what we can and cannot do and how we can and cannot imagine our collective pasts. To enter the rescpritive space, we must start by descripting the past. More than describing, desciripting means that we assess the holes, margins, edges, and even the spaces between the words and letters of the Historical scripts pages to make new meaning. If at its heart description is based on describing the fact or experience, the act of descripting history is a call that we look more closely at the complexity of those two categories and realize that the scriptive things we are working with can never be whole. Despite this paradigm, we are whole as we exist now. As such, the rescriptive space asks that we conscript ourselves in the historical narrative. This is what descripting does.

The rescriptive space is the space where we have the potential to frame or flatten the scriptive thing, but instead look at it from all dimensions, angles, and distances we can imagine and instead choose to perform, or performatively engage it differently. Instead of looking back at History as an inactive audience, we become not only an active audience, but its script writers and co-performers. This is more than historical improvisation. Improvisation has a set stage and set props. Entering the rescriptive space means going off script and leaving not just the stage behind, but the theatre as well. The new theatre is the space where you exist now, not the space where you go to be conscripted, by invitation or intention, for a set period of time. The stage is the entire world. History as scriptive thing demands and requires your presence. Being off script happens passively here. The here and now of off-scriptedness is the temporal-spatial realm where we can begin to engage rescriptive things and practices.

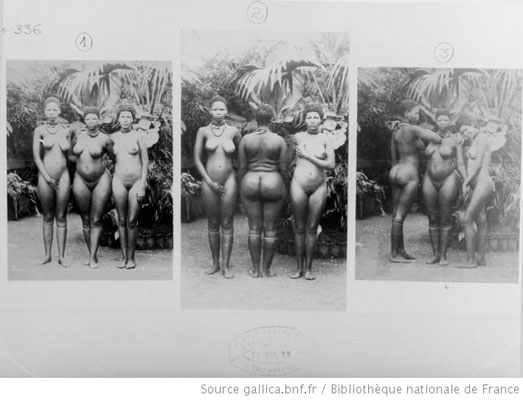

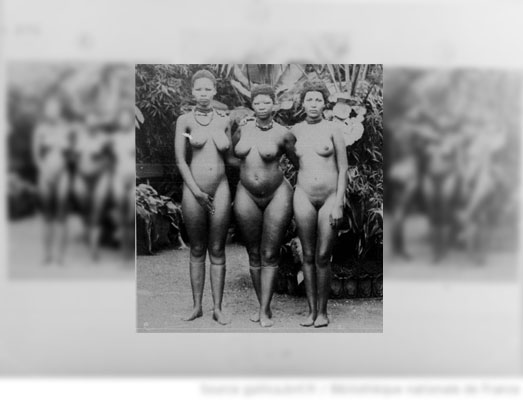

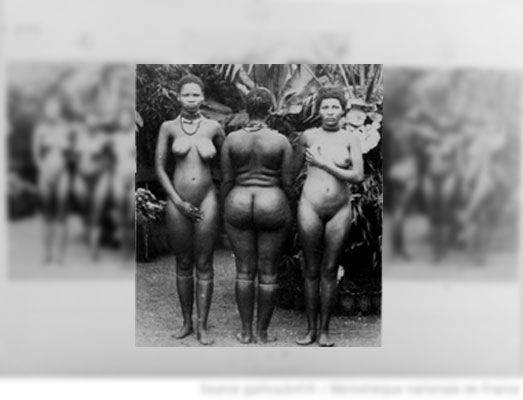

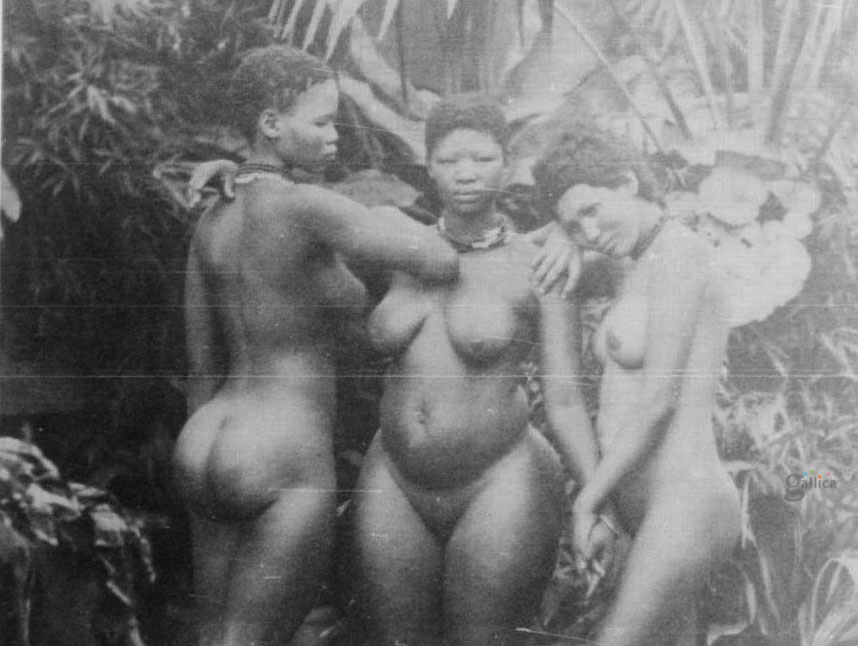

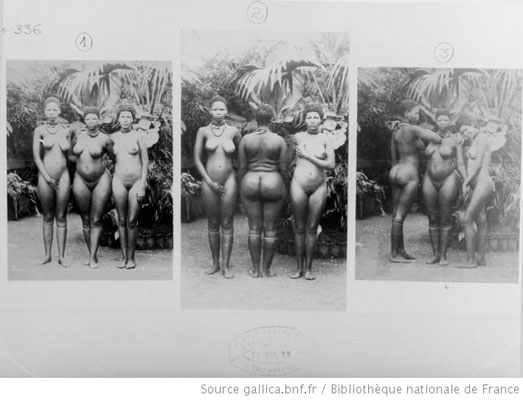

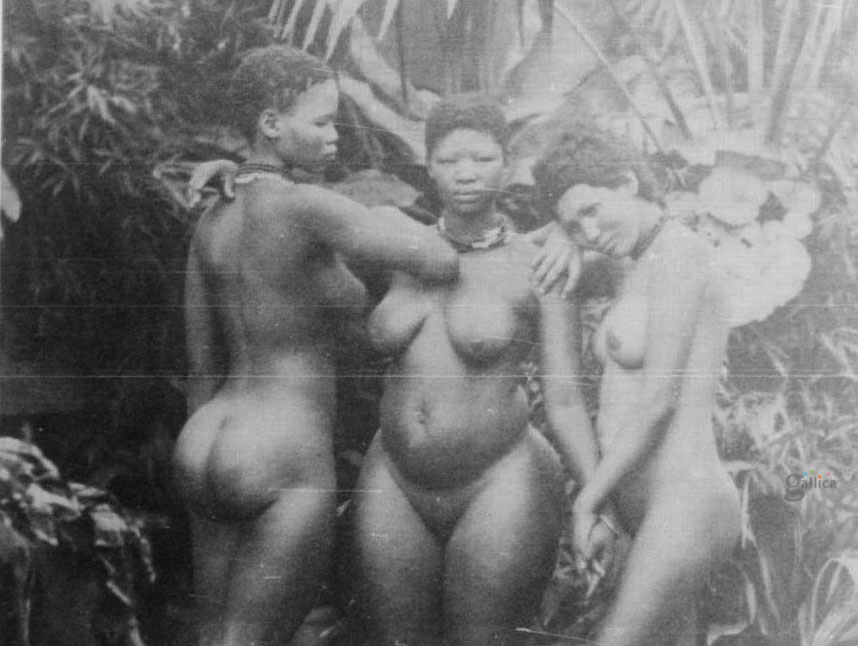

For the purpose of my project, the historical thing that makes up the scriptive thingness of History is old photographs of colonized and post slavery (but not so post that the memories of that time were just memories) black female subjects. By sharing these photos in a digital format, a format that is already rescriptive as it changes our interaction with the photographic object, and sharing these photos across time and space, both the time and spaces of those women photographed and ours, and positioning these women as beautiful, their history is descripted. If I tell people about my project, for instance, if I were to describe the Hottentots from 1889 as three naked black women from South Africa who had their photo taken because of the size of their hips and butts, specifically to be put on display at the colonial exposition in Paris, people will cringe and be uncomfortable. However, when you see the photo, the experience is different. Specifically, I think the 3rd photo in the set changes how we see these women.

The intimate position of the three women in the third picture, with the woman on the left turned slightly back to ensure we see her full backside, resting her arm on the shoulder of woman in the middle as she looks towards the third woman. The woman in the middle has her hand lightly draped over the shoulder of the woman on the far right, she is turned almost completely forward so we can see the entire front of her body, looking directly at us through the screen. On her other shoulder, the woman on the right leans, hand over shoulder, head one hand. Her other hand holds the woman in the middles other hand. Their fingers are entwined. She is turned to one side to ensure we can see what her body looks like from the side. Instead of looking at us, her eyes are slightly angled down. Coupled with her head resting on the her hand, her body leaning into the woman in the middle, her belly against the other woman’s arm, we are left with the impression she is tired and leaning on her companion in this photo. In all three photos, these women’s bodies are intertwined to some degree, but in photo 3, we get a feeling of closeness and safety that is not quite present in photo 1 & 2. This intimacy that we are being invited to be conscripted in by viewing the photograph forces us to not see these women as an exhibit, even if that was the original purpose of the photograph. Instead, we descript the situation, and see the women as women. We rescript them as whole people, capable of having agency, relations, and lives outside of the colonial history and exploitation scripting that brought them to us.

Once digitized and dispersed not as a material object that fades away over time, but instead as instantaneously reproduced data and light, we are able to let go of the historical thinggyness that wrote the script before. We move off-script. We see the beauty of this moment and then trouble the past. We see the beauty of these women despite the original script. We see the beauty of our ability to imagine them differently because the prescription of the digital allows us to remember the past rescripted. In doing so we rescript history towards an alternate prescription. If the photographs of women in my project existed to visually describe the other, to write them down and fix them. The act of descripting in the digital allows for theses women to exist outside of that moment. We know they had lives because they’ve become a memory in ours and that new memory is not marred by the shadow of colonisation, but instead by that moment of encounter when we saw these women and thought “beautiful”.

In thinking of larger social implications of what conscripting women from across the black world, time, and space, in one digital project where they exist as a whole, my hope is to model not only what the black woman diaspora feels like, but also what it looks like. The project is not an act of community building, but rather an attempt at creating a communal space where descripting and rescripting can begin to happen. By affectively engaging with these women, by not only encountering, but being confronted with the depth and diversity of experiences that were captured and placed in the archives, that are now being digitized we are able to see these women had lives. The intent in sharing these photos is not to create a feeling of nostalgia. They are not about looking back to a better time or place. Looking at these photos is not about all the “what could have beens.” Rather, these photos exist to help imagine and discover what could be. Looking at these photos is about rescripting diaspora not as linked by tragedy, trauma, and crisis, but instead looking at this diaspora for the beauty, infinite potential and varied experiences it has always been. Even as blackness interpolates black women into universal western scripts, we have never only been these things. We are, and have always been, so much more. This simple acknowledgement rescripts History.

ARTICLE

Bernstein, Robin; "Dances with Things: Material Culture and the Performance of Race"; Social Text 2009 Volume 27, Number 4 101: 67-94

PHOTO

"Hottentots", album de 19 phot. anthropologiques de femmes hottentotes présenté à l'exposition universelle de 1889 à Paris. Des collections du prince R. Bonaparte. Enregistré en 1929, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Société de Géographie, SGE SG WE-336

http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b7702319b

Tumblr Post:Hottentots, 1889